Chapter 10: Understanding player input

Actions originate from the parser, a central part of the standard library. This chapter describes how to extend the parser to understand new kinds of sentences.

Grammar definitions

Player input is mapped to actions using (grammar $ for $). For

instance, the following definition causes TAKE A NAP to be

recognized as an attempt to perform the [sleep] action:

(grammar [take a nap] for [sleep])There is no automatic rule for recognizing the words that make up the internal name of the action, so the following definition is probably also desired:

(grammar [sleep] for [sleep])But in this case, there is also a shorthand form:

(grammar [sleep] for itself)Slash-expressions are useful:

(grammar [sleep/nap/dream] for [sleep])The left-hand side of a grammar definition may contain special tokens,

standing in for objects. Thus, [object] represents an arbitrary

object in scope, or even many objects (separated by commas or AND).

On the right-hand side, a wildcard ($) indicates the place in the

action where the object is supposed to go:

(grammar [buy/purchase [object]] for [buy $])Alternatively, [single] represents a single object in scope.

Attempts to specify multiple objects are then rejected with:

(You're not allowed to use multiple objects in that context.)A grammar definition can contain multiple tokens, which are then mapped to the wildcards in left-to-right order. It is recommended to restrict all except one of them to a single object, to prevent combinatorial explosion. Thus:

(grammar [read [object] to [single]] for [read $ to $])or:

(grammar [read [single] to [object]] for [read $ to $])Sometimes you want the tokens mapped to wildcards in right-to-left order. Use

(grammar $ for $ reversed) for that:

(grammar [lend [object] to [single]] for [lend $ to $])

(grammar [lend [single] [object]] for [lend $ to $] reversed)The basic set of grammar tokens are:

- [object]

-

One or more objects in scope.

- [single]

-

A single object in scope.

- [any]

-

A single object, not necessarily in scope. The object must be located in a visited room, and cannot be marked as hidden.

- [direction]

-

One or more directions, such as

NORTH,DOWN, orOUT. - [number]

-

A number, such as

FIVEor1981. - [topic]

-

A topic (see Ask and tell).

In addition to the above, you can guide the parser towards certain classes of

objects, to help resolve ambiguities as well as decide what the word

ALL refers to. The following constraints are not enforced

strictly—you must use (prevent $) rules for that.

- [animate]

-

A single, animate object in scope.

- [any animate]

-

A single, animate object, not necessarily in scope. For e.g.

CALL MOTHER. - [single held]

-

A single object currently in the player’s inventory.

- [held]

-

One or more objects currently in the player’s inventory. Special feature: If the player supplies

ALLhere, then the single object matched by the next grammar token (if any) is excluded from the set of objects. - [worn]

-

One or more objects currently worn by the player.

- [takable]

-

One or more items in scope, whose relation to their parent is neither

#heldby,#wornby, or#partof. Furthermore, they shouldn’t be nested below an object that’s held or worn by a non-player character, or nested below the current player (regardless of relation).

Finally, a list of words that isn’t recognized as a special token will match any of the words in the list. This results in slightly faster and more compact code than a slash expression, but either syntax is fine, really. The following two definitions are functionally equivalent:

(grammar [throw/toss [held] at/on/to/in/into/onto [single]] for [throw $ at $])

(grammar [throw/toss [held] [at on to in into onto] [single]] for [throw $ at $])Grammar rules must start with a regular word, typically a verb. Tokens and other lists are allowed everywhere else, just not at the very beginning.

Adding actions

(grammar [yodel] for itself)Here the story author has introduced a new action, [yodel],

triggered when the player types YODEL. But so far, there is no code

to handle the action. The fallback implementations of the six

action-handling predicates will cause the

action to succeed without printing anything at all. This is a no-no in parser

games, so the story author should at least add a

perform-rule:

(perform [yodel])

Your voice soars over the mountain tops, bringing tears to many eyes.Action descriptions

The standard library might have to print the name of an action, perhaps as part

of a disambiguation question, or during debugging if the ACTIONS ON

command has been issued. This is done with a query to the predicate

(describe action $).

Usually, there is no need to add an explicit rule for describing every new

action; the default implementation of (describe action $) simply visits

each element of the action (which is a list) in turn, printing dictionary words

verbatim, and calling (the full $) for anything else. But sometimes a

better wording is desirable:

(describe action [switch on $Obj])

switch (the full $Obj) onCommands

Commands are system-level actions, such as SAVE or

TRANSCRIPT OFF, that do not consume any time in the game world. The

predicate (command $) decides whether an action is a command or not.

Thus, to define a new command called HINT, we could write:

(grammar [hint] for itself)

(command [hint])

(perform [hint])

Try yodeling a lot.There is also a short form that combines the first two rule definitions into one:

(understand command [hint])

(perform [hint])

Try yodeling a lot.Asking for clarification

Some actions are designed to require objects, but it makes grammatical sense to

use the verb alone (intransitively), or with fewer objects than the author had

in mind. For instance, a grammar definition could be added to recognize

PLAY VIOLIN WITH BOW as the action

[play #violin with #bow]:

(grammar [play [single] with/using [held]] for [play $ with $])But now, players who type PLAY VIOLIN (or just PLAY)

will be met by an unhelpful message about not understanding what they wanted to

do. In this case, it’s a good idea to add partial actions that nudge the player

towards the full sentence. These actions can ask the player for clarification,

and set up an implicit action using one of the predicates

(asking for object in $) and (asking for direction in $). The parameter is an

action, with an empty list [] marking the position of a blank slot.

If the player now types in the name of an object (or, optionally,

USE followed by the name of an object), this will be understood as

the implicit action, with that object in the slot. Thus:

(grammar [play [single]] for [play $])

(perform [play $Obj])

With what?

(asking for object in [play $Obj with []])

(grammar [play] for itself)

(perform [play])

Play what?

(asking for object in [play []])Be aware that (asking for object in $) and

(asking for direction in $) will automatically invoke (stop) to prevent any

subsequent actions: We’ve asked the player a question, so we have to give them

an opportunity to respond.

Of course, it is also possible to override your own action-handling rules for this kind of intermediate actions, in specific situations where no additional object is required:

(perform [play #piano])

You plink away at the Maple Leaf Rag, only to get stuck in the trio.Just remember that rules are tried in program order, so the rule for playing the piano must appear before the generic perform-rule that asks for a second object. One approach is to organize the story file as a large bulk of object-specific rule definitions, followed by a smaller section at the end where new actions are defined.

A note on rule ordering

You are encouraged to define plenty of synonyms using slash-expressions and multiple grammar definitions. Here is an example from the library:

(grammar [leave/exit [single]] for [leave $])

(grammar [get/jump/go [out off] of [single]] for [leave $])

(grammar [get/jump/go off [single]] for [leave $])Such definitions can appear in any order. However, if you define multiple grammar rules that begin with the same words, but produce distinct actions, then you should put the longest rule first:

%% Understand PLAY VIOLIN WITH BOW, or PLAY VIOLIN, or PLAY:

(grammar [play [single] with/using [held]] for [play $ with $])

(grammar [play [single]] for [play $])

(grammar [play] for itself)This makes a difference when the player has typed something that the parser

doesn’t understand. When that happens, the library constructs an error message

from the first grammar rule that is a partial match. Given the above code, if

the player types PLAY SPICCATO WITH BOW, the response will be:

(I only understood you as far as wanting to play something with the bow.)But if the first two rules were swapped, the parser would match

SPICCATO WITH BOW with the sole parameter of

[play $], and the following message would be printed instead:

(I only understood you as far as wanting to play something.)Adjusting the likelihood of actions

When the player’s input can be understood in multiple ways, it is up to the game

to weigh the different interpretations against each other, and select the one

most probably intended by the player. This is achieved by looking at the actions

from a semantic point of view, and discarding the unlikely ones, as determined

by the predicate (unlikely $):

(unlikely [open $Object])

~(openable $Object)

(unlikely [open $Object])

($Object is open)If that’s not enough, and several equally likely (or unlikely) interpretations remain, the library will ask the player a disambiguating question.

Thus, if the player is located in a room with a wooden door (open), and holds a

wooden box (closed), and attempts to OPEN WOODEN, that will be

understood as a request to [open #woodenbox]. The alternative,

[open #woodendoor], gets discarded due to the second rule

above. But if both the door and the box are open, both actions are deemed

equally unlikely, and the game resorts to asking the player what they meant.

Story authors may override (unlikely $) to influence this proceduce.

For instance, if a room contains a red lever and a red indicator light, it’s up

to the author to specify:

(unlikely [pull #redlight])which makes PULL RED do the expected thing.

Sometimes it is necessary to override (unlikely $) with a negated rule,

when a more general rule would identify it as unlikely by default. For instance,

suppose a location contains a wall-mounted ladder, and the story author wants

the game to understand CLIMB LADDER as going up. The functionality

itself is implemented by redirecting [climb #ladder] to

[go #up]:

(instead of [climb #ladder])

(current room #ladderroom)

(try [go #up])But [climb #ladder] is still considered unlikely by the parser,

because (we assume) the ladder is not an actor supporter, i.e. it is not

possible to be located #on the ladder. Now, if the player were to

attempt to CLIMB LADDER while also holding the ladder instruction

manual, the game would ask which one of the objects to climb. To prevent that

slightly surreal question, a negated rule can be defined:

~(unlikely [climb #ladder]) %% Climbing the ladder is not unlikely after all.Very unlikely actions

In Dialog, the current room and its neighbours are in scope by default. But

rooms are often named by some conspicuous object contained inside them, so that

e.g. an engine might be located in the engine room. To avoid a lot of

disambiguating questions, any action that explicitly mentions a room is

considered (very unlikely $) by default, unless it’s one of the few

actions that might involve a room (such as [enter $] or

[go to $]).

This predicate rarely needs to be touched outside of library code. But if you

ever add a new action that involves a room object directly, make sure to adjust

the rules for (very unlikely $) as well as (unlikely $).

Links and default actions

When a Dialog program is compiled to run on the Å-machine, the text may contain clickable links that resolve into text input. Selecting a link has the same effect as typing the words of the link target and pressing return. This can simplify text entry on mobile devices.

Links are created using the special (link $) … syntax:

In the bowl a (link [red marble]) { red marble } glistens in the sunlight.Often, as above, we want both the link target and the clickable text to be the same. In this case a short form is available:

In the bowl a (link) { red marble } glistens in the sunlight.If we want both the link target and the clickable text to be the printed name of

an object, we can use the tersely named predicate ($) from the standard

library:

In the bowl a (#redmarble) glistens in the sunlight.The same predicate can be used for exits:

An exit leads (#north).To use the printed name of an object as a link target, but supply a different

text, use the predicate ($ $). The first parameter is an object, and

the second is a

closure:

In the bowl (#redmarble {something red}) glistens in the sunlight.Be aware, however, that hyperlinks are an optional feature of the Å-machine, and not every interpreter will support them. While it can be tempting to create a jarring effect by having links resolve into unexpected input text, some players will simply not see it.

By default, library-generated messages never contain hyperlinks. The behaviour of the library should be consistent with the rest of the story, and whether or not to sprinkle room descriptions with clickable links is a decision best left to the author.

To enable clickable links in disambiguation messages, the game over menu,

default

appearances,

and queries to (a $)

and (A $), add the following rule definition to the source code:

(library links enabled)Since link targets are appended to the current line of input, readers who are playing on a touchscreen device can type a verb using the on-screen keyboard, and then complete the sentence by tapping on a recently printed object name. Compass directions can of course be used directly as commands.

However, when we turn our nouns into hyperlinks, players will (understandably) attempt to click on them without first typing a verb. To handle this situation, the standard library provides an optional feature called default actions. It is enabled like this:

(default actions enabled)When this feature is enabled, the parser will understand noun-only input as a

request for the default action, which is examine. The default action

can be changed, and may depend on the object, as in the following example:

(default action (animate $Obj) [talk to $Obj])Example: Defining a new action

Story-specific actions are typically defined towards the end of the source code file. This allows object-specific rules, defined earlier in the file, to override them.

The following example relies on a special property of the

[held] token: When the first token of a grammar rule is

[held] and the player uses ALL in that position,

then whatever matches the second token is excluded from the set of objects.

Thus, if the player types PEEL ALL WITH PEELER, the

ALL will expand to every held object except the peeler. Note that

this may still not be what the player intended (because in addition to fruit,

they might be holding a brass key and a lamp), but at this stage we are

primarily interested in grammar, not semantics.

Remember, put the longest grammar definition first:

(grammar [peel [held] with/using [single]] for [peel $ with $])

(grammar [peel [held]] for [peel $])

(perform [peel $Obj])

With what?

(asking for object in [peel $Obj with []])Either variant is deemed unlikely for non-edible objects:

(unlikely [peel $Obj | $]) %% Match both variants.

~(edible $Obj)The likelihood of an action helps resolve ambiguities, but it won’t prevent the action from being attempted: If the player unambiguously tries to peel the kitchen floor, that request is going to go through, unlikely or not. Thus we also need:

(prevent [peel $Obj | $])

~(edible $Obj)

That's not something you can peel.Likewise, because we specified [held], the library will try to

satisfy the parser rules using objects that are held by the player, so that e.g.

PEEL FRUIT will prioritize held fruit over non-held fruit. But an

unambiguous PEEL BANANA will be understood even when the banana

isn’t held.

Thus, we need a rule to prevent the peeling of a non-held object. The standard library provides a number of handy when-predicates that check for common conditions, and print appropriate responses when the conditions are met.

(prevent [peel $Obj | $])

(when $Obj isn't directly held)

(prevent [peel $ with $Obj])

(when $Obj isn't directly held)But, out of the kindness of our hearts, we might decide to pick up the mentioned objects automatically before attempting the peel action:

(before [peel $Obj | $])

%% This will invoke (first try [take $Obj]) if necessary:

(ensure $Obj is held)

(before [peel $ with $Obj])

(ensure $Obj is held)Finally, there needs to be a default response for the

[peel $ with $] action (we already have one for the [peel $]

action):

(perform [peel $Obj with $Tool])

After an extended period of fumbling, you conclude that you don't know

how to peel (the $Obj) with (the $Tool).

(tick) (stop)Of course, the story should also contain a couple of objects that would make the peel action succeed. The following object-specific rules must be defined before the generic rules described above, otherwise they will never match:

(edible #apple)

(edible #peeled-apple)

(perform [peel #apple with #peeler])

You peel the apple without cutting yourself even once.

(#apple is $Rel $Loc)

(now) (#apple is nowhere)

(now) (#peeled-apple is $Rel $Loc)Finally, we could smoothen gameplay by implicitly assuming that if the player is holding the peeler, that’s probably their tool of choice for peeling:

(instead of [peel $Obj])

(current player $Player)

(#peeler is #heldby $Player)

\( with the peeler \) (line) %% Tell the player what's going on.

(try [peel $Obj with #peeler])How the parser works

This section provides an outline of how the parser works, and describes advanced techniques for understanding arbitrary turns of phrase that cannot be represented by ordinary grammar definitions. Most story authors do not need to dig this deeply, and can safely skip ahead to the next chapter.

The parser makes queries to (understand $ as $), a predicate that is

normally defined by the library, but which can also be extended by the story

author. One of the library-defined rules for this predicate is responsible for

querying the table of grammar definitions. But there are also rules for special

cases like GO TO ROOM, or ACTOR, COMMAND. We

will discuss how to add such special cases.

During parsing, the standard library works with an intermediate representation of actions, called complex actions. Like regular actions, complex actions are lists of dictionary words and objects, but the following subexpressions are also allowed in them:

- [+ #object1 #object2 …]

-

The player referred to multiple objects here.

- [a #object]

-

The player referred to a non-specific object that should be printed with “a” rather than “the”.

[a …]subexpressions may be nested inside[+ …]subexpressions. - []

-

The input contained one or more words that couldn’t be parsed. When the complex action is printed, this part will appear as “#something”.

- [1]

-

The input contained one or more words that couldn’t be parsed, and an animate object was expected. When the complex action is printed, this part will appear as “someone#.

- [,]

-

The input contained multiple objects in an illegal place.

- [all]

-

The input contained an

ALL-expression in an illegal place.

Thus, a complex action might be:

[give [+ [a #apple] #peeler] to [1]]and its printed representation makes an appearance in the following message:

(I only understood you as far as wanting to give an apple and the peeler to

someone.)The parsing process

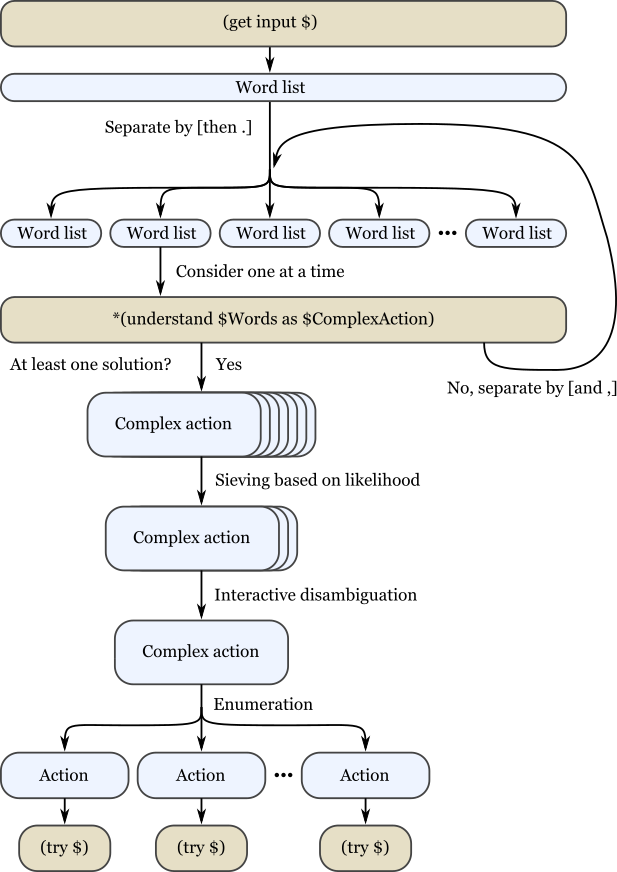

The following chart illustrates the overall parsing process, starting with the

player input as a list of words, and ending with a set of actions. The list of

words is first split into a sequence of sublists by the word THEN

or the full stop. If such a sublist cannot be parsed, it is in turn split by the

first AND or comma. This allows the player to type multiple

commands on one line, such as: N, U THEN DROP ALL, D.

Parsing actions

When the library needs to parse an action, it makes a

multi-query to

(understand $ as $). A multi-query is made in order to collect every possible interpretation

of the player’s input, which could be ambiguous.

The first parameter is the input: a list of dictionary words. The second parameter is the output: a complex action.

Story authors can easily add rule definitions to this predicate, in order to add support for new verbs or set phrases (although in this case, a normal grammar definition would also work):

[give [+ [a #apple] #peeler] to [1]]Note that the multi-query to (understand $ as $) may backtrack over

several possible interpretations, e.g. [wait] and

`[take #break] if an object called “#break” is

in scope.

Understand-rules may of course have rule bodies:

(understand [who am i] as [examine $Player])

(current player $Player)Parsing object names

Many actions involve objects. The rule for understanding such an action will

typically query a library-provided predicate for parsing a list of words as an

object. There are several to choose from, but the most basic one is

(understand $Words as non-all object $Object), which can be used like

this:

(understand [transmogrify | $Words] as [transmogrify $Object])

*(understand $Words as non-all object $Object)Note that a

multi-query must be used,

because the words may be ambiguous. Suppose a red box and a blue box are in

scope. TRANSMOGRIFY BOX will cause the above rule header to match,

binding $Words to the single-element list [box]. Since

there are two boxes,

(understand [box] as non-all object $Object)

will return twice, binding $Object to #redbox the

first time, and to #bluebox the second time. Consequently, the rule for

understanding the action will return twice, binding its output parameter to

[transmogrify #redbox] the first time, and

[transmogrify #bluebox] the second time.

Some actions involve two (or even more) objects, usually separated by a keyword such as a preposition. Dialog provides a handy built-in predicate for searching a list for a set of keywords, and splitting the list at the position where a match was found. Consider the following example, where a new “read something to somebody” action is created:

#book

(proper *)

(name *) To Kill A Mockingbird

#bird

(animate *)

(name *) mockingbird

(understand [read | $Words] as [read $Object to $Person])

*(split $Words by [to] into $Left and $Right)

*(understand $Left as non-all object $Object)

*(understand $Right as non-all object $Person)Again, the consistent use of multi-queries helps with disambiguation. If the

player attempts to READ TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD TO MOCKINGBIRD,

$Words will be bound to

[to kill a mockingbird to mockingbird].

The `split-#predicate first separates it

into [] and [kill a mockingbird to mockingbird].

The empty list is not a valid object name, so the subsequent query to

(understand $Left …) fails, and the split-predicate proceeds with

the next occurrence of the keyword: Now it separates $Words into

[to kill a mockingbird] and [mockingbird],

which makes the rest of the rule body succeed.

Still, the name of the second object (MOCKINGBIRD) is ambiguous, so

the final invocation of *(understand $Right …) returns twice.

The parser will end up asking the player whether they wanted to read the book to

the bird, or the book to the book. One way to address this problem is to

indicate that the second noun is supposed to be animate:

(understand [read | $Words] as [read $Object to $Person])

*(split $Words by [to] into $Left and $Right)

*(understand $Left as non-all object $Object)

*(understand $Right as single object $Person preferably animate)The library provides a set of object-parsing predicates that favour objects with certain common traits, or limit the selection in some other way. The object-parsing predicates are:

-

A predicate that accepts multiple objects, but not the word

ALL:(understand $Words as non-all object $Output) -

Predicates that accept multiple objects, including

ALL:(understand $Words as object $Output preferably held)

(understand $Words as object $Output preferably held excluding $ExcludeObj)

(understand $Words as object $Output preferably worn)

(understand $Words as object $Output preferably takable)+(understand $Words as object $Output preferably child of $Parent) -

Predicates that only accept a single object (possibly implied by

ALL):(understand $Words as single object $Output)

(understand $Words as single object $Output preferably held)

(understand $Words as single object $Output preferably animate)

(understand $Words as single object $Output preferably supporter)

(understand $Words as single object $Output preferably container) -

Predicates that accept any (single) object, even if it’s currently out of scope, as long as it’s located in a visited room and not hidden:

(understand $Words as any object $Output)

(understand $Words as any object $Output preferably animate)

Some of the variants above are primarily there to provide context for the word

ALL. For instance, TAKE ALL should only select

takable objects (items not already held), while DROP ALL should

operate on held objects. But the preferably specifier is also used to

carry out some initial disambiguation, so that e.g. FEED BIRD might

be understood as an intention to feed the bird (animate), but not the bird cage.

Three further variants allow the story author to specify an arbitrary condition using a closure:

(understand $Words as object $Output preferably $Closure)

(understand $Words as single object $Output preferably $Closure)

(understand $Words as any object $Output preferably $Closure)

The closure takes a candidate object as parameter. Here is an example of how to parse an object name while favouring objects that can be picked up, but not eaten:

(understand $Words as object $Obj preferably {

(item $_)

~(edible $_)

})The output of all of these object-parsing predicates is either an object or a

list that represents a complex object (e.g.

[+ $Obj1 $Obj2 $Obj3], or [a $Obj1], or []) For the

as single object rules, the output is guaranteed to be either an object

or one of the values that indicate a parse error.

Directions, numbers, and topics

Some actions involve a named direction, such as SOUTHWEST,

OUT, or UP. To parse a direction, use the predicate:

(understand $Words as direction $Dir)As when parsing objects, $Dir is potentially a complex expression: When

the player types PUSH CART SOUTHWEST, OUT AND UP, the words

[southwest , out and up] will be understood as the complex

direction [+ #southwest #out #up].

To parse a number, typed using decimal digits or spelled out as a word, use:

(understand $Words as number $N)The output parameter $N is a

number

thus limited to the range 0–16383.

Topics

Some actions, e.g. [ask $ about $] and

[tell $ about $], involve topics of conversation. As we saw in the chapter about

non-player characters, topics can be regular objects,

topic objects, or dictionary words. To parse a topic, use the predicate:

(understand $Words as topic $Topic)It is possible to add rules to that predicate in order to add new topics to a game:

(understand [my childhood] as topic @childhood)

(understand [growing up on planet zyx] as topic @childhood)However, that would result in a parser that is very picky about the exact wording of ask/tell commands, so it is not generally recommended. A better (but potentially slower) approach is to look for keywords or key phrases like this:

(understand $Words as topic @childhood)

($Words contains sublist [growing up])

(or) ($Words contains one of [childhood planet zyx])The default implementation of (understand $ as topic $) tries to strike

a balance between performance and flexibility by using a system of simple

keywords. Keywords are defined with (topic keyword $ implies $):

(topic keyword @childhood implies @childhood)

(topic keyword @zyx implies @childhood)A short form is available when the keyword equals the topic value:

(topic keyword @childhood)All of these variants can of course be combined. For instance, the keyword approach could be employed as a fall-back that often works well enough, and specific understand-rules could use the '(just') keyword to overrule the keyword system when it would otherwise misfire:

(understand [your childhood] as topic #doctor)

(just)

(topic keyword @childhood)

(topic keyword @yourself implies #doctor)The (just) keyword can also be used to selectively disable the

behaviour where objects in scope are understood as topics. For instance, in an

aquarium, the word FISH might be accepted as a synonym for every

individual fish in the room. But suppose we want the last word of

ASK CLERK ABOUT FISH to be understood unambiguously as being in

reference to the general subject of fish. That is, suppose we don’t want the

game to ask the player if they meant to ask about fish in general, the

zebrafish, or the neon tetra. To obtain the desired behaviour, we just have to:

(understand [fish] as topic @fish)

(current room #aquarium)

(just)Printed representations of topics

Topics are supposed to have printed representations, accessible via the

(describe topic $) predicate. The default implementation of this

predicate delegates to (the full $) when the topic is an object;

otherwise it just prints the word “something”. Story authors are strongly

recommended to override this predicate for non-object topics:

(describe topic @childhood)

your childhoodWhen you add new actions that involve topics, remember to add corresponding

(describe action $) rules as well. That’s because the default

implementation of (describe action $) is rather crude: It looks at each

element of the action list, printing full descriptions of any objects, and

printing dictionary words as they appear. But if the dictionary word happens to

be a topic, the proper thing to do is to query (describe topic $) to

print it. Thus:

(understand [complain about | $Words] as [complain about $Topic])

*(understand $Words as topic $Topic)

(describe action [complain about $Topic])

complain about (describe topic $Topic)Rewriting

Before the player’s input is handed to the action-parsing predicate

(understand $ as $), it undergoes rewriting: The predicate

(rewrite $Input into $Output) is queried once (i.e. neither iteratively

nor with a multi-query), and may transform the list of words in any way it sees

fit before parsing.

(rewrite [please | $Words] into $Words)Rewriting is not used by the library itself, but it offers a powerful way for story authors to override the default behaviour of the parser.

Custom grammar tokens

This section explains how to add new grammar tokens, like

[worn] or [single held]. It’s an advanced

topic, and most story authors can safely skip ahead to the next chapter.

Let’s create a [spell] token, to be used like this:

(grammar [cast [spell]] for [cast $])

(grammar [look up [spell]] for [consult #spellbook about $])

(understand [xyzzy] as spell #xyzzy)

(understand [plugh/abracadabra] as spell #plugh)Recall (from How the parser works) that the

library defines a generic (understand $ as $) rule that queries a table

of grammar definitions. This table is called (grammar entry $ $ $), and

it is constructed at compile-time from instantiations of the

(grammar $ for $) access predicate.

A definition like the following:

(grammar [give [held] to [animate]] for [give $ to $])is transformed into the following table entry:

(grammar entry @give [22 to 11] [give $ to $])The first parameter of the grammar entry is the first word of the grammar rule.

This helps the compiler create efficient lookup code. The second parameter

corresponds to the rest of the grammar rule, with numeric values instead of

symbolic tokens (e.g. 22 instead of [held]). The third

parameter is the action template, exactly as supplied in the grammar definition.

There are two reasons for translating the grammar tokens into numbers: It makes the code more compact (and therefore faster on old systems), and it prevents the grammar tokens from cluttering the game dictionary.

Grammar tokens are converted to numbers using a set of access predicate

definitions in the standard library. For instance, here is the rule for

converting [direction] to 50:

@(grammar transformer [[direction] | $Tail] $SoFar $Verb $Action $Rev)

(grammar transformer $Tail [50 | $SoFar] $Verb $Action $Rev)It operates by removing one element from the incoming list (first parameter), tacking on a new element to the outgoing list (second parameter), and leaving three more parameters intact.

Numbers in the range 90-99 are reserved for story authors. To create our new

[spell] token, we add a similar rule to map the token to an

unused number in this range:

@(grammar transformer [[spell] | $Tail] $SoFar $Verb $Action $Rev)

(grammar transformer $Tail [90 | $SoFar] $Verb $Action $Rev)Next, we supply a rule for what to do when the number 90 is encountered in the grammar table:

@(grammar transformer [[spell] | $Tail] $SoFar $Verb $Action $Rev)

(grammar transformer $Tail [90 | $SoFar] $Verb $Action $Rev)In the above example, we delegate to a separate custom predicate for handling

spells. Under other circumstances, we might have queried an existing predicate

such as *(understand $Words as object $Obj preferably { … }).

The third parameter of (match grammar token $ against $ $ into $) is

rarely used. It contains matches from later grammar tokens (they are parsed from

right to left). These can be objects, plus-prefixed lists like

[+ #foo #bar #baz], or anything else; it depends on the

type of the next token. This feature allows you to craft rules for e.g.

PUT ALL IN BAG, where the bag should not be included in “all”.

TODO:

-

Indentation for

(understand …)predicates using closures